He shares his knowledge of SaaS metrics and economics on his blog, TheSaaSCFO.com, where all of his SaaS models are available for free download.

SaaS companies are fond of their metrics, but where do you start as a leader in your organization? When you have four ways to calculate customer lifetime value, it’s easy to throw in the towel before you even pick up your monthly income statement.

With a lot of things, the hardest part is knowing where to start. To truly assess the health of your SaaS business, you must dive down below your standard financial statements and calculate metrics specific to your SaaS business.

The following five metrics, I’ll call the Famous Five, are important for SaaS companies beyond the startup stage. As a CFO in an ARR-driven SaaS company, I look at these five metrics at least monthly. But if you invoice monthly and have numbers that change weekly, you’ll want to calculate them more frequently.

1) MRR/ARR

Let’s start with an easy one.

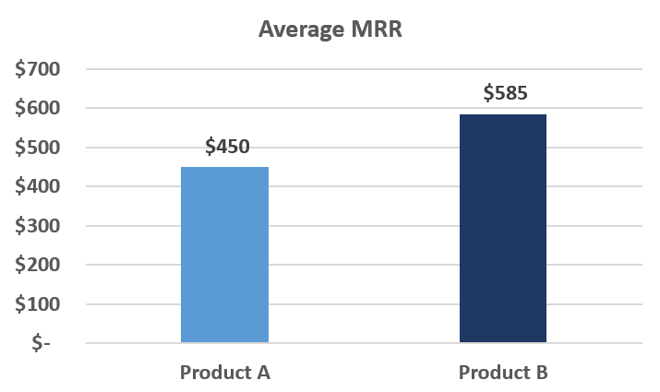

Every SaaS company should be measuring their monthly recurring revenue (MRR) or annual recurring revenue (ARR). You should know your average MRR or ARR per customer and your recognized MRR (per your income statement).

Also, let’s not confuse bookings (an executed software contract) and recognized MRR. Bookings is not a GAAP or IFRS term, but simply a measure for your signed software contracts. Make sure you are speaking on the same terms with your team. If I said we booked 100K, is that ARR or MRR? Be consistent with how you measure your subscriptions.

MRR/ARR is a building block and used in many other SaaS metric formulas. If you have different product lines, you should calculate MRR or ARR separately for each product, because averaging them together will not provide the true picture.

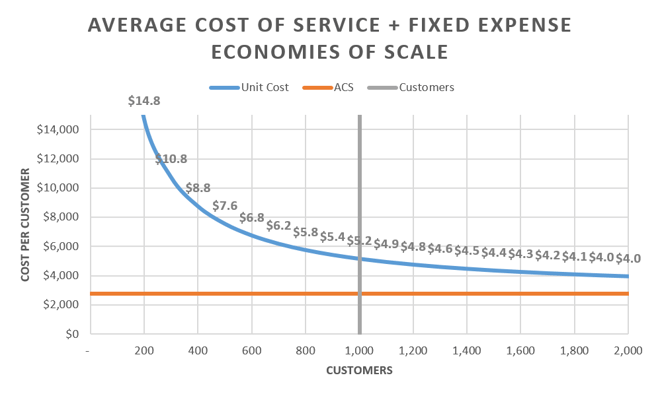

2) Average Cost of Service (ACS)

This is one of my favorites.

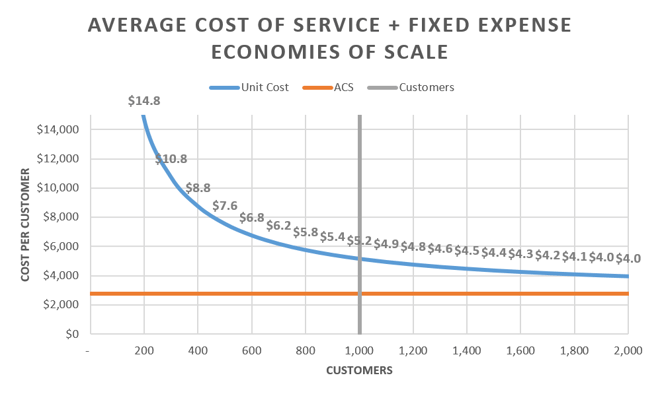

ACS tells you how much it costs to serve your existing customers. When I say “serve”, I mean delivering the software, providing support, upselling additional features, making your customers successful, and so on. ACS isolates the departments and expenses on your P&L that support your existing, recurring revenue stream.

Here’s an example of why I love ACS and what I have experienced firsthand. If your sales team is closing deals at or just above your average ACS, you’ve got trouble. If you are selling below your ACS, game over.

Depending on your CAC, customer profitability might never be reached, because high CAC and thin margins on ARR or MRR minus ACS mean a long payback period. Churn will make this worse.

I calculate ACS using the following components:

- R&D Amortization – the economic cost of your current release(s). If you don’t capitalize development, then the full cost of your R&D department.

- Technical Support - typically, your call center handling inbound customer questions.

- R&D Net of Cap – I look at the expenses in my development cost center and exclude software capitalization. What remains, in my mind, is the cost of software maintenance and supporting current releases. Not new development.

- Account Management – the sales team responsible for taking care of current customers.

- Hosting – your hosting and data center costs.

- Customer Success – I could see this as either 1) an ACS expense or 2) embedded in your Service department and counted in your service margins.

3) Cost of Customer Acquisition (CAC)

3) Cost of Customer Acquisition (CAC)

We’ve all heard of CAC and for good reason: it’s a critical metric.

Simply put, CAC is the total sales and marketing expenses associated with acquiring one new customer. Measure this by product and for your different acquisition channels.

$$\frac{\text{Sales and Marketing Expense}}{\text{New Customers Acquired}}$$

When I say sales and marketing expense, this includes wages, taxes, benefits, travel, meals, and any expense on your P&L that goes towards landing new customers. CAC is powerful when compared to ARR from a customer.

If your accountant or controller is not doing this already, make sure you are coding expenses and headcount to the department level on your general ledger. This is a must or most SaaS metrics will be almost impossible to calculate and you won’t understand the health of business.

A parting note on CAC: the length of your sales cycle matters for this calculation. If you have a 12-month sales cycle, don’t just take the last three months of expense to determine your CAC. Include the timeframe of expenses that are representative of your sales cycle.

4) CAC Payback Period

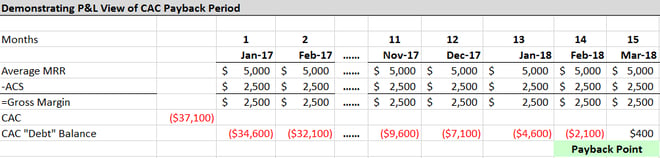

What if I were to say that every time you acquired a customer, you were taking on debt?

In this case, the debt is CAC. Whether the customer stays or churns, this debt stays with your business until it is paid off.

Crazy, right? That money has been spent even if the customer churns. You’ve got to pay it back now. The more churn, the more new customers you need to pay off your existing debts. That’s why CAC is a critical metric and length of time it takes to pay back CAC is the natural extension of this concept.

In my view, the CAC Payback Period is the number of months required to pay back the upfront customer acquisition costs after accounting for the variable expenses to service that customer. Simply put, CAC Payback Period equals CAC divided by the gross margin dollars generated by that customer.

$$\text{CAC Payback Period}=\frac{\text{CAC}}{(\text{MRR}-\text{ACS})}$$

You will not be profitable with that customer until you have paid back CAC. Then your margin will be your MRR less ACS. That is the contribution margin to your business from that customer.

5) Customer Lifetime Value (LTV)

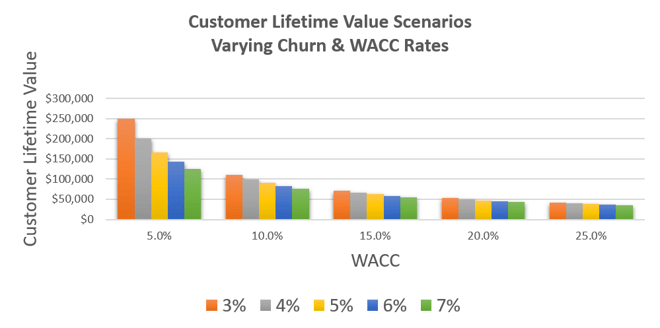

Remember when I said there are four ways to calculate LTV? Well, there are many ways, but let’s jump to my favorite LTV formula. The formula I use to calculate LTV is below.

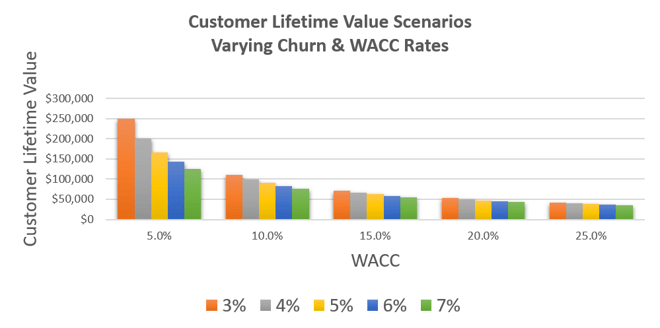

$$\frac{\text{Annual Recurring Revenue}-\text{Average Cost of Service}}{%\text{ Churn}+\text{WACC}-\text{ Subscription Increase}}$$

For me, this formula reveals the lifetime margin (factors in ACS) of one customer after discounting for the time value of money (WACC) and churn but offset by customer subscription growth.

Very wordy, I know. To put it in another context, think business valuations. Instead of valuing the cash flow of a business, you are valuing the cash flows produced by one customer.

I’ve got LTV, now what? Now, compare your LTV number to your CAC. Industry guidance suggests your LTV should be three times your CAC.

SaaS metrics are much more meaningful when used together to paint a picture. And notice how this formula requires two of the metrics explained above, ARR and ACS.

Takeaways

Takeaways

Whew, we made it through the Famous Five.

Incorporate these five metrics into your monthly financial reporting package and your financial discipline will begin to improve. You’ll have a better understanding of your business and you’ll be able to take proactive measures to improve the health of your SaaS business.

3) Cost of Customer Acquisition (CAC)

3) Cost of Customer Acquisition (CAC) Takeaways

Takeaways